So with everyone talking about TV in that film, I thought I should mention that more but what I find more interesting for myself (and in the future when we watch The Conversation) is that idea of surveillance, private/public, and emasculation not just through gazing on the television but through being gazed at by the mechanical apparatus.

Let's start with the hotel room. So here is a place where light is paradoxically both denied and allowed. Keenan talked about the Panopticon imprisoning through an excess of light, which is what occurs in a certain sense for Oh Daesuh's 15 year home; he's under constant surveillance, constant watch, and we see later the man at the desk having a television monitor peering into every room. Also, although he lacks literal windows his room contains one very important window which everyone is talking about, the TV, the window into the public world. That TV informs OhDaesu of everything he learns, but the TV in the film also shows us the spectator moments of Korean/International history happening over those 15 years (death of Princess Di, the scandal of Korean presidents, etc). So just as much as it's a nurterer, emasculator, and companion, it is also "light" bleeding from the outside to the inside, serving to make his prison public and private. So just as his entire life in the prison is public, his companion in a sense is the public conscious, Korean TV. What does Korean TV do? As everyone said before me more or less, it emasculates/hypermasculates him.

Now his life is a "larger prison". He is still watched, there is an excess of light (and color) in his new prison, his private actions are recorded, gazed at, in a sense public. He is still under panoptic gaze, still subjectified. Just as he is being followed by the diegetic gaze of the photographic camera and the recording device. But at a meta level, the film camera is also following his movements, he may or may not be on display but cannot escape our gaze, the camera gaze. At the same time, he has to enact punishment, sexuality, etc. on the female; throughout his relationship with MiDo he almost rapes her, ties her up and distrusts her, and alternates between punishing and loving her until the sexual act is commited between the two (but even then she is still punished, locked up 'for her own safety'). But those actions turn to punish HIM in turn, that those vouyeristic pleasures/fetishizations and classic hollywood romances serve as his ultimate punishment, where we finally watch the long drawn out process of the male being punished. And as we reassure that the female is castrated in classic cinema, we see OhDaesu "castrated" as he cuts out his tongue on screen. And just as the older brother in The Aimless Bullet turns away, so do we all cringe at the cutting of the tongue, perhaps the most intense moment of the film. But then what I'm not sure about is this: does Oh Daesuh enact a 'reverse' oedipal fear? Or perhaps he is afraid of MiDo realizing she's enacted some transgressive Oedipal process, that she has not followed the 'proper' Fruedian process? Or made love to an emasculated man (is somehow a deviant sexuality, not just in incest but also a homosexual)? Perhaps then his castration means less if he is already monstrous, like the crippled men of The Aimless Bullet.

See, this is just coming off the top of my head. If I sat down for like, half an hour longer I could have 15 more pages of crap to say about this movie.

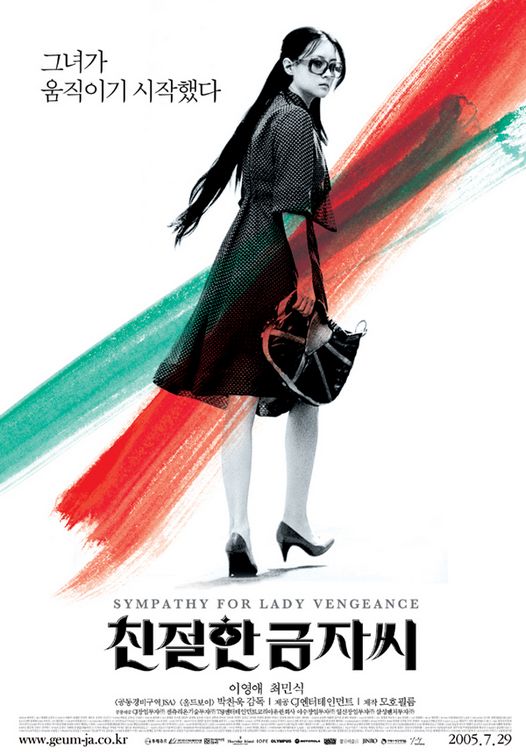

In conclusion, I love OldBoy. But perhaps not as much as Sympathy for Lady Vengeance.

Good Stuff.